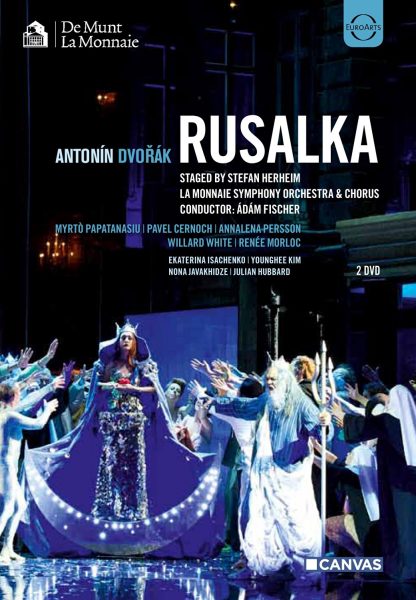

Even if one dislikes Regietheater, one must acknowledge that Dvorak’s Rusalka has been recently well served by thought-provoking and beautiful stagings, most notably Martin Kusej’s poignant production for the Bavarian State Opera, available on DVD, but also Stefan Herheim’s for La Monnaie and the Oper Graz, presently being revived in Brussels. As always with the Norwegian director, the audience is supposed to be familiar with the libretto to follow his x-ray incursion into the inner structure of an opera and its psychological, symbolic, historical, you name it associations. As much as I find all his points valid and insightful, I am afraid one has to overlook some heavy-handedness now and then, especially the suppression of the act III scene with the gamekeeper and the kitchen boy* to fit the director’s superimposed plot, the constant manipulation of dialogues (a great part of lines are said to the benefit of a character other than the one specified by the author, what requires some mind-boggling two-level action on stage) and most of all artificial references to the aquatic nature of the fairytale that seem rather an after-thought than something in the core of his concept.

As it is, Herheim’s Rusalka is a study of the violence and abuse inflicted on woman by the way men expect them to conform to their fantasies about them. In order to show this, the Prince becomes the image of the Water Sprite as a young man and Rusalka, the Foreign Princess and Jezibaba the projections he makes on two real women: his wife and a prostitute he fantasizes about. Thus, a middle-aged man sees this young hooker who teases him as he is about to get into his house, but his wife sees it, believes that he was after her and locks him out. Indignant, he attacks the young woman and, under the shock of the situation, blurs the lines between fantasy and reality. In his vision, he is haunted by his desire as a young man for an innocent bride in a white gown, by his frustration as married man with a distant wife, by the dream of a woman as entirely conceived by a man’s mind (materialized as a female character in an opera – here the Queen of the Night from Schinkel’s 1816 Berlin production) and by apparitions of women undesired by men (old hags, nuns, witches…) before he actually kills his wife and handles her as a puppet. At the end, the prostitute sings Rusalka’s last lines to the corpse of the murdered woman. One may ask what the mermaid and her prince have to do with it, but I would say that probably everything. Herheim’s view of the incompatibility of what women are and what men want them to be probably in the bottom of the myth of dangerously seductive mermaids confined in their waterworld in comparison to the safety of dry land. I wonder if one really needs such a convoluted scheme to make the audience see that, but Herheim does know how to make his complex ideas work on stage, by virtue of beautiful and imaginative sets, many coups de théâtre and his keen understanding of the score.

“Keen understanding of the score” are words one could use about conductor Adám Fischer, who offered an ideal account of Dvorak’s music this evening. His orchestra played warmly and richly in dense Romantic style and absolute structural clarity and even the comparatively kitsch episodes with the water nymphs sounded vigorous and colorful rather than cute and sprightly. This score has many shifts of mood and Fischer could find unusual coherence and organicity in it. He had a very good cast, crowned by an admirable performance from Myrto Papatanasiu in he title role. The Greek soprano has the perfect voice for it – her fruity full lyric soprano can scale down to floating pianissimo or build up to exciting acuti most naturally. She gave me the impression of being in absolute control of her resources and commands a great range of tonal coloring and does it in the service of drama. She is also a good actress and has a beautiful figure for this role. Annalenna Persson makes an interesting contrast as the Foreign Princess in her steely soprano that lacks however some warmth and roundness. Maybe it is Dolora Zajick’s fault that after seeing her as Jezibaba, I always dream of a dramatic mezzo in that role. Renée Morloc is not exactly that, but she does have big low and high notes and negotiates her passaggio quite efficiently. She is an intense singing actress who knows how to keep you interested in what she is doing. Pavel Cernoch’s typically tight Slavic tenor predictably makes more sense here than in Italian repertoire. He still finds the role of the prince a bit heavy, but sings cleanly and with very clear diction. Although Willard White’s bass baritone is a bit rusty, it is still commanding in its richness and darkness. The production demands a lot from him and it is most welcome that he would avoid hamming and prefer a more self-contained approach that comes more naturally for him. Small roles were all of them very well sung.

* I have to confess that the distribution of the gamekeeper and kitchen boy’s lines in act II to a variety of characters invented by Herheim actually made the scene more interesting than I usually find it.

Source: https://ihearvoices.wordpress.com/2012/03/15/dvoraks-rusalka-la-monnaiedie-munt-14-03-2012-35